A calculation on electricity rates in the South American country determined that only in eleven more years could citizens see relief in their electricity supply bill, according to academic Ronald Fischer.

The phrase "there is no free lunch" could be making more sense than ever in Chile this month.

In July there was the first of three increases - two more will come in October and January - in the electricity supply accounts and, since such a measure was inevitable, the accusations were crossed between the Boric government, the Piñera government, parliamentarians and political parties. has not ceased.

Just this day the Minister of Energy, Diego Pardow, has come out to deny that the information about this increase was hidden from public opinion. The truth is that it has been known for almost five years, but only now is it being taken into account.

This has made Pardow today face a possible constitutional accusation from the opposition for the drastic increase of almost 60% in electricity bills that will affect both regulated, or home, clients, and unregulated, or industrial clients.

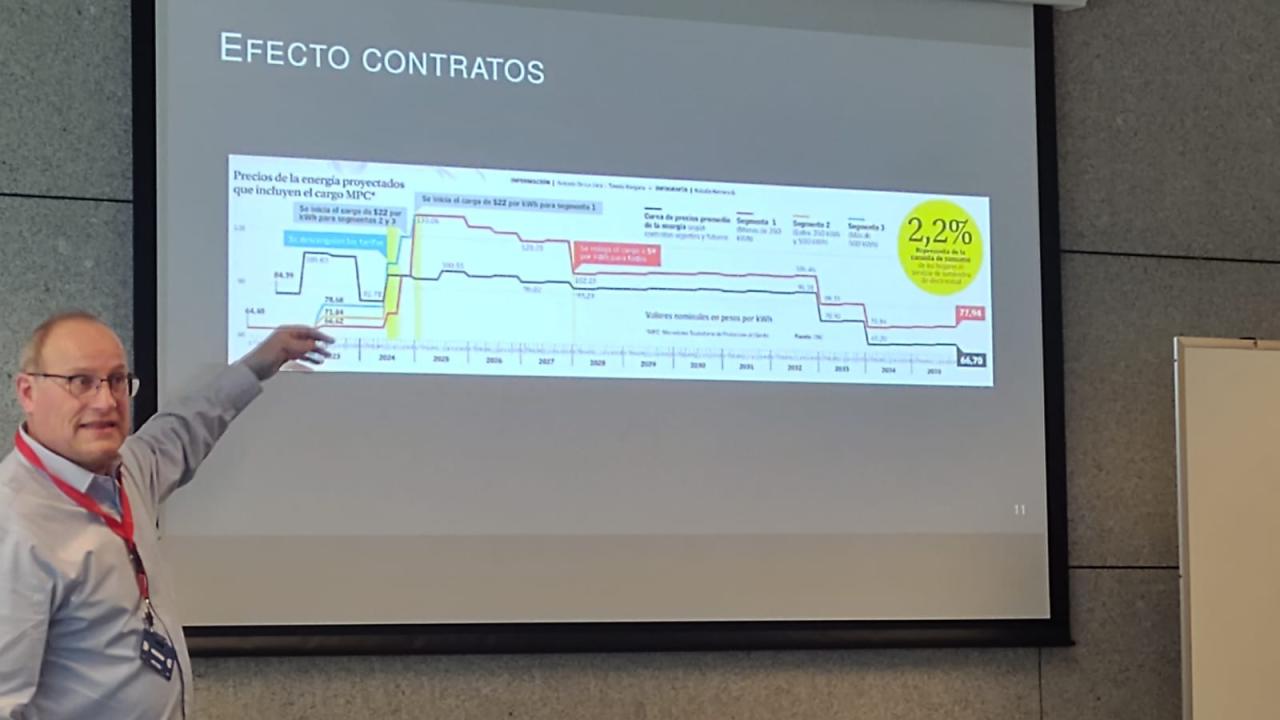

What is clear is that such increases - which could even derail the Central Bank's 3% inflation goal - are not going to stop until 2035, when the debt with the Chilean energy sector stops being paid, at a rate of 22 pesos (US$ 0.02) per kilo watt consumed (the average for a home in Chile is 270 to 350 kilowatts per month) just as interest on the debt.

FROM THE DOLLAR TO THE UKRAINE WAR

As in everything, the first explanation is to find those responsible. But here the list is long and complex, since the Chilean electricity sector has several actors and many ways of calculating the costs at which electricity is purchased and paid for.

Trying to simplify, it was in 2019 when electricity in Chile should have increased in price, but the political moment of the social outbreak and then the pandemic made it unviable. So, for more than four years, the rates were maintained, at the expense of companies in the sector: many companies began to have losses, or very low profitability.

"Simply what the government [of the time] did was tell the firms 'don't raise the rate' and they couldn't disconnect people who didn't pay either," explains academic Ronald Fischer, an academic at the Center for Applied Economics (CEA). ) of Industrial Engineering from the University of Chile, to AméricaEconomía .

The government's goal was to let time pass and, when electricity rates began to drop due to the greater presence of clean energy and new supply contracts, instead of lowering them, leave them at the same value to make up for the period that had existed. elapsed without registering increases for end customers.

The plan was: maintain the price and return to companies when they enter lower priced contracts, which would occur when the debt reached US$1,235 million.

Thus, any increase would not be felt as much in the pockets. But the government did not take into account the external factors that occurred during those years, the academic points out. "The war in Ukraine came, the CPI rose, the dollar rose, the value of oil rose..." explains the academic from the industrial engineering department.

So everything happened like in an avalanche of snow: the original deadline to resist any increase ended much earlier than expected, and prices were still high when there was still a long way to go before the values of electricity generation began to fall, which affected the incoming Boric government as well.

"The new government maintained prices for another two and a half years and today the debt with companies reaches US$6 billion. Companies in the sector were beginning to falter, they could not survive, they were going bankrupt and, in the end, they had to be honest. that," says Fischer.

The result is an enormous cost for generators and distributors, which is just beginning to be paid, with hundreds of millions of dollars owed and with the publication of the 2025-2028 tariff decree still pending, because the distribution tariff decree that corresponded to 2020-2024 is published very recently.

NO WAY OF SOLUTION

Immediately, the race for a bill subsidy is unleashed, with proposals such as a surcharge on the green tax, a surcharge on the public service charge that today is paid especially for large electricity consumption and a greater tax contribution via the higher collection of value added tax.

But the economic sectors also blame the blow, saying that the cost of this subsidy should not be burdened on an already ailing economy.

And if it is bad news, Chileans should prepare for another dose of reality, since this increase that would end in 2035, when the debt is paid off, would be recalculated taking into account the price that corresponds to the value of the contracts. But that "does not include the other things that may have increased [in that period], such as [electrical] distribution that has to increase as well (...) So the impact is going to be stronger than that."

That is what is coming for the country: distribution has the prices of eight years ago, since the tariff decree that corresponds to 2020-2024 was recently promulgated. "So there is, taking inflation plus the debt of non-payments, we would have to pay more for distribution as well. Let's add to that that in transmission more investments must be made, because solar plants are often in the north and need to be transmitted to consumption centers," concludes the academic.