Sheinbaum wants to replicate Mexico City's electric transportation networks at a national level, Gálvez seeks to collaborate with municipalities, and Álvarez aims to create a “green tax.”

A month before Mexicans go to the polls, the three leading presidential candidates agree on the importance of an energy transition to counteract dependence from Pemex crude oil, meet the objectives of COP28 and, in the long term, alleviate the effects of pollution and climate change.

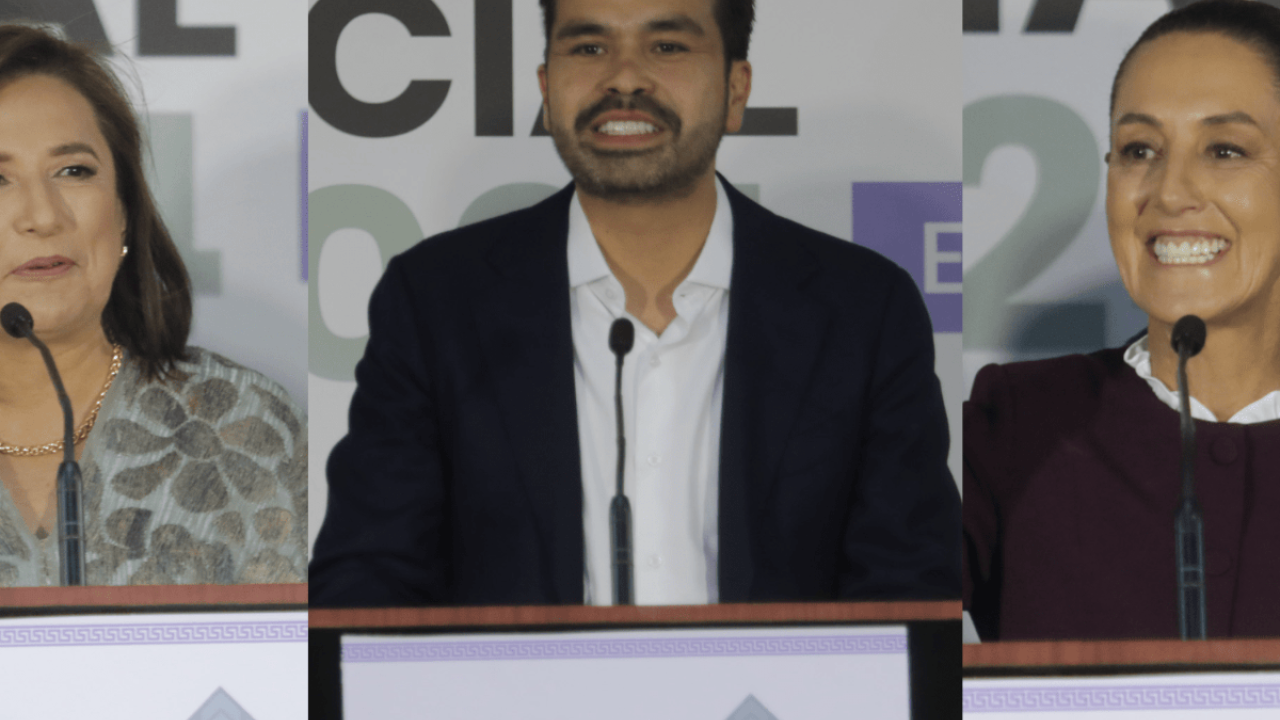

Apparently, there is a consensus between the speeches of the government's candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum, the opposition's, Xóchitl Gálvez and the outsider, Jorge Álvarez. In reality, as usual, the difference is not what, but how. This became evident in the second presidential debate, held on April 28 focused on economy, inequality and climate change.

For staters, Álvarez Maynez, who is third in the latest Mitofsky survey with a modest 9.3% vote intention, proposed the creation of a green tax, whose funds would be allocated to promote electromobility in public transportation. To this end, the current Special Tax on Production and Services (IEPS) --which is paid for the production, sale or import of gasoline and diesel in Mexico-- would be modified.

Álvarez supports using the funds to expansion electrical transportation networks nationwide, such as those currently being built in the states of Jalisco and Nuevo León. Meanwhile, southern regions such as Oaxaca and Yucatán, where poverty is high, would benefit from “clean and cheap” energy projects such as wind and solar.

Similarly, Claudia Sheinbaum, a leftist candidate for the ruling Morena party, committed to generate 50% of Mexico's energy through renewable sources by 2030. It is a goal that Xóchitl Gálvez also shares, not by mere chance: it was one of the objectives agreed during the last COP, held in the United Arab Emirates at the end of 2023.

Regarding electromobility, Sheinbaum aspires to replicate the electric public transportation initiatives that she developed during her period as mayor of Mexico City. These are projects such as the trolleybus, the cablebus, as well as the supply of electric vehicles on lines 3 and 4 of the Metrobús.

To achieve the goal, her administration would seek to facilitate the development of infrastructure, regulations required for electromobility, and promote the sale of zero-emission vehicles, among others. To distance hersefl from the oil focus of president Andrés Manuel López Obrador's six-year term, Sheinbaum's electromobility aspires to be the new norm of transportation promoted by the Mexican government.

“There is a clear difference in betting on electromobility of private units and a social one that understands the complexity of climate change and how public transportation policy has to focus on this type of projects that benefit many and make efficient use of public resources,” says Tonatiuh Martinez, an economist member of Claudia Sheinbaum's team, in an exclusive interview with AméricaEconomía .

Meanwhile, Héctor Moreno, also from Sheinbaum's team, is optimistic about nearshoring due to the imminent construction of new automotive plants in Mexican territory from BYD and Tesla --leaders in electromobility.

On the other hand, during the debate, Gálvez stressed her support for electromobility, although without delving into its features. Among her public policies as president of Mexico, the opposition candidate would use gas as the main transition fuel and thus convert Pemex into an energy company in general. Subsequently, the senator also highlighted that she would support the efforts of the automotive industry to produce and adopt electric or hybrid vehicles on an accelerated basis.

Rosanety Barrios, energy analyst on the Xóchitl Gálvez team, clarifies that close collaboration with local authorities and diversification of energy sources is needed to promote electromobility.

“We want to collaborate with municipalities so that everyone has the possibility of developing their electromobility, in terms of public transport. One of the arguments why it is said that these plans are not yet applicable is the electricity shortage. Because yes, we live without electricity. So, they also do not allow private initiative to take charge of its own energy. Anyway, the model is closed today to private participation. It did not comply with its obligation to invest in transmission and distribution,” Barrios declared to AméricaEconomía .

The analyst describes the energy policy of the López Obrador government as “completely centralized” and one where “no one can have a say in anything.” She stresses again collaboration with state and local governments to overcome energy shortages. “States and municipalities have the best idea of what their energy problems are, but also their solutions. All states have an energy agency or undersecretary of energy. So that important human capital has already been developed that knows how to act in the future,” says Barrios.

In order to take advantage of this capital, the analyst proposes what she defines as close collaborations with states for the purposes of energy planning and project development. Barrios considers that 21st century energy emphasizes production where it is generated and consumed. This is the only way to achieve the goal to build 30 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2030.

From the Sheinbaum team, the strategy to promote renewable energies in rural areas of Mexico is aimed at raising awareness about the value of the energy transition among the population. “Part of the doctor's (Sheinbaum) social package in the energy sector involves organization with the communities. We plan to send technicians to the localities that do not speak technical language, and rather raise awareness of the case and listen to the needs of the population. Financing is also very important and will be paid for by the government,” explains Tonatiuh Martínez.

For his part, Ramsés Pech, energy analyst and associate professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) , considers that although rural communities do not usually have high energy consumption in their homes, they do require it to cook food through firewood. It is an input that emits greenhouse gases and this has a negative impact on the health of farmers as it emits ashes to homes.

“I think that instead of thinking about how to get electricity at home, we should visualize a way of how they can be part of the transition, by leaving fuels that they have traditionally used and see how to make them more efficient. Currently, there are ecological kitchens and some of them have replaced the high consumption of firewood,” said Pech for AméricaEconomía