The goal is to create a model that will give the Atacama indigenous groups, also known as the Lickanantay, an active role in the new project on a salt flat that stretches across one of the driest places on the planet.

Chile's indigenous communities in the lithium-rich Atacama Desert are in talks with two of the country's largest mining companies to gain more influence over plans to increase extraction of the battery metal, according to the companies and community sources.

The negotiations with Chilean state-owned Codelco, the world's largest copper producer, and Chilean lithium producer SQM come as the companies close to finalizing a partnership that would mark the state's entry into production of the metal crucial for electric vehicle batteries.

Talks to develop the so-called "governance" plan began in March and are expected to conclude by the end of the year, Reuters has learned exclusively. These talks follow a dialogue initiated last year in which the companies explained the joint venture and community representatives expressed their concerns.

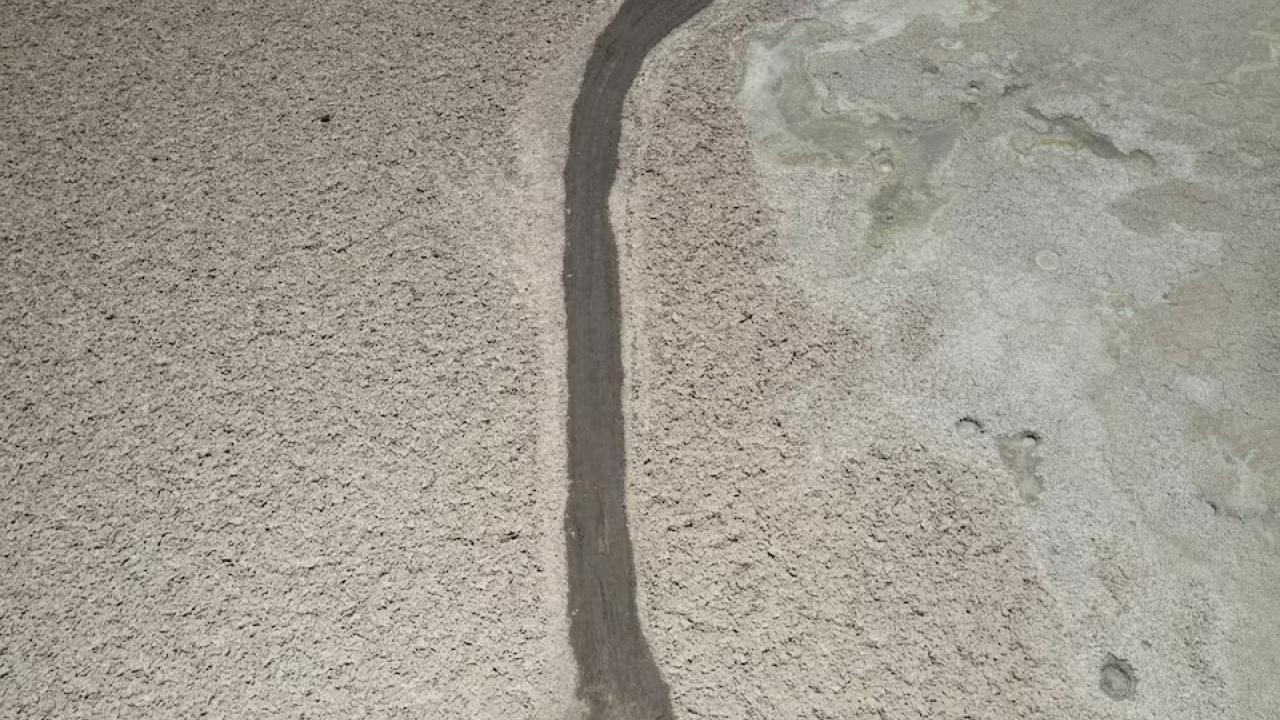

Both sides say their goal is to create a model that will give the Atacama indigenous groups, also known as the Lickanantay, an active role in the new venture on a salt flat that straddles one of the driest places on the planet, where people have lived for thousands of years.

"We have invited them to work together on a governance model that effectively recognizes and considers the perspectives and visions of the Lickanantay communities in the decision-making processes of the new company," Codelco and SQM said in a joint statement to Reuters .

The companies called the potential system "unprecedented" in Chile, adding that it would comply with international treaties on indigenous rights.

During Reuters visits to five indigenous villages in the Andean foothills above the salt flats, community leaders emphasized the need to hold SQM and Codelco accountable for their environmental commitments, particularly limiting water use.

"The idea is that it's not just the company that decides what to do in our territory," said Sergio Cubillos, a community leader from Peine, which overlooks the vast Atacama Basin, which provides a quarter of the world's lithium supply.

Giving Indigenous groups a seat at the table could potentially reduce profits if it led to more costly environmental standards.

At the same time, a deal could be attractive to global buyers who are increasingly focused on ethical mining to meet shareholder demands and help avoid protests.

The mining sector sees the protests in Panama in 2023 that led the government to close First Quantum Minerals' copper mine as a warning.

“Companies have realized that halting production obviously has a detrimental effect,” said Yermin Basques, a leader of the Toconao community.

One option for a new framework would be regular dialogue with company decision-makers, such as board members, Basques said.

"This would allow us to participate in the discussion about how the technological extraction process will work, how we will safeguard the water supply, and how we will develop extraction with a lower environmental impact ," he said.

Obtaining a board seat isn't the goal, he noted, since communities don't seek a voice in business decisions.

Dialogue with Codelco and SQM had been tense at times, Basques added, but the two sides were now working together, in part because the companies recognized the need for community support after protests hampered SQM's logistics last year.

We have specific knowledge of our territory and our waters. And we have the authority to close the salt flat if necessary.

THE CLOCK KEEPS TICKING

Codelco and SQM told Reuters that talks will continue this year, building on dozens of meetings last year with Atacama groups.

Their joint venture, in which Codelco will hold a 50% stake plus a controlling stake in SQM's operations in Atacama, is scheduled to enter into force in the second half of the year, pending regulatory approvals.

An advisor to the Atacama Indigenous Council (CPA), which comprises 18 communities, told Reuters that the council was reviewing initial proposals for the governance model, including one submitted by Codelco and SQM, but declined to provide details.

The companies declined to provide their proposal to Reuters, citing the ongoing process.

The advisor said council representatives will meet with Codelco and SQM every two weeks for the next two to three months while they develop a final proposal.

Each community will then discuss the plan internally, before representatives agree on a final version with Codelco and SQM, expected in the second half of the year, the advisor said.

Codelco and SQM plan to increase lithium production by up to 33% through 2060. The goal is part of a tectonic shift in Chile’s lithium sector after leftist President Gabriel Boric announced plans in 2023 to shift to a state-led model, spearheaded by Codelco, and committed to prioritizing Indigenous rights.

Some community leaders say they feel a sense of urgency to reach an agreement with Codelco and SQM while Boric is in office until March of next year, concerned that a successor could shake up the country's lithium strategy and move away from Boric's pro-indigenous stance.

Some legislators from various parties have criticized the Codelco-SQM agreement, concerned that it would benefit Chile. Most opposition presidential candidates have yet to define their position on lithium mining. By law, Boric cannot run for a second consecutive term.

"We have to hurry, because we don't know what might happen next year," said Basques, a Toconao leader.

Veteran conservative politician Evelyn Matthei, who is currently leading in the preliminary presidential polls, said in a statement from her office to Reuters that she supports mining development, wants to boost Chile's lithium production, and aims to benefit all people, including indigenous communities.

Chile's Mining Ministry declined to comment on the Codelco-SQM venture.

NEW MODEL

Chile has the largest proven lithium reserves in the world, according to data from the United States Geological Survey, and is the second-largest producer after Australia.

While some Indigenous groups in Canada and Australia have taken a greater role in environmental management, such practices are rare in Latin America, experts say.

SQM shareholders, as well as clients focused on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks, such as European automakers, are likely to view an indigenous deal as positive for SQM, said Seth Goldstein, an analyst at Morningstar Research Services.

“Dialogue allows SQM an easier path to keep its operations running,” he said.

SQM already implements indigenous outreach programs, including working groups, reporting channels, joint environmental monitoring, and cooperation agreements. In some communities, the company has installed solar panels, provided dental care, and offered agricultural training.

SQM's efforts follow best practices for community relations, according to a 2023 audit by the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), an assessment process favored by electric vehicle manufacturers to ensure supply chain transparency.

Still, the audit found that SQM still had work to do to overcome years of mistrust.

Winder Flores, who grew up in the village of Talabre and now helps his elderly mother make cheese and wool crafts in Tambillo, near the edge of the Atacama salt flat, is aware of the stakes.

"We want the miners to guarantee us that there will be no pollution, that we won't run out of water," he said, as his herd of goats and llamas wandered through one of the desert's rare grazing areas, fed by a freshwater spring.

"We're not against the country's development, but we do want to be part of it and not be left with nothing."